Chapter 12.7 Obtain best production from rainfall received

Chapter 12.7 Obtain best production from rainfall received

Background information

This chapter outlines what you need to know about the more prevalent vertebrate pest animal species and how to use this information to effect control of the pests which are relevant to your business.

This chapter contains links to the most up to date information on managing vertebrate pest species to ensure you get the most effective control for investment of your time in controlling these animals. Use the links to further your level of knowledge and understanding of the pest species you are targeting.

Without a basic understanding of the key times for strategic baiting and other control agents, and the positive impacts that working in a coordinated fashion can have on decreasing populations, your time may be not spent effectively.

At a glance

- Effective vertebrate pest species management requires careful planning to optimise control of animals.

- Target times of the year to effectively manage one or more species in a single program.

- Aim to work in a coordinated fashion in a regional context for enhanced control of predator species.

Rainfall is the key driver of production in all grazing management systems. To ensure that the rain that falls is efficiently converted into sufficient quantity and quality of feed, the pastoral production system and business which operates on it must be in a ‘rain ready’ state. This requires that when the rain falls on the property, it soaks into the soil and the property and business are each in a state whereby they capture productivity that the rainfall will provide.

Rain stimulates growth of palatable and productive ephemeral, annual and perennial species. This plant growth provides energy, protein and key elements to achieve favorable levels of livestock production.

In this context, the level of production from the property could be measured based on both land area and rainfall received by considering:

- DSE per hectare per 100 mm of effective rainfall

- Kilograms of meat or wool produced per hectare or square kilometre per 100 mm of effective rainfall

- Other measures such as productivity per DSE (this could be expressed as $/DSE, GM/DSE or Profit/DSE)

- Other measures relating to NRM outcomes (such as percentage groundcover at key dates).

These performance indicators can then be measured and monitored to assess annual production efficiency. Using rainfall as part of a performance indicator can add valuable context to poor seasons, by allowing you to measure performance in below average rainfall seasons, in the context of rainfall received.

There are four must-dos in this procedure:

- Be rain ready for your business and property.

- Know your options in good seasons.

- Know your options in poor seasons.

- Monitor your business.

Be ‘rain ready’ for your business and property

Rain ready property

Landscape function provides a measure of the landscape’s capacity to capture rainfall and nutrients that directly contribute to plant growth and productivity in the system. Landscape function provides an assessment of landscape condition and resilience.

A key step in ensuring you are ‘rain ready’ is to ensure your pasture is conditioned in a way to manage the next rain event, and just as importantly, to manage through dry times.

Maintaining landscape function ensures pastures are ready to respond to the next rain event. Conditioning pastures to respond to rainfall involves strategies such as maintaining adequate cover levels and managing to maintain perennials in the system. Ground cover assists rainfall infiltration and efficient nutrient cycling. By managing the utilisation of perennial grasses to the recommended rates, you are maintaining landscape function, allowing responsiveness, and also keeping a mix of perennials in your pastures. Perennial grasses are important for maximising sheep production and rain use efficiency. They respond (produce green leaf) to summer storms and survive between infrequent showers.

Similar to landscape function, the ‘land condition gateway’ of the Gateways Model from Grazing Land Management (developed for northern pastoral areas), considers the capacity of the land to respond to rain and produce useful forage and is a measure of how well the grazing ecosystem is functioning.

There are three components to consider in determining the level of functionality of the land system.

- Soil condition is an assessment of the soil’s ability to:

• Absorb and store rainfall;

• Store and cycle nutrients;

• Provide suitable conditions for seed germination; and

• Resist erosion. - Pasture condition is an assessment of the feedbase to:

• Capture and store solar energy and produce palatable green leaf;

• Use rainfall efficiently;

• Contribute to soil stability; and

• Cycle nutrients. - Woodland condition is an assessment of the woodland to:

• Grow pasture;

• Cycle nutrients; and

• Regulate groundwater.

Minimise overgrazing and decline in landscape function

Overgrazing can negatively impact the rain readiness of your property. Excessive populations of domestic, feral and native grazing animals combined with dry conditions when feed levels are reduced have been primary contributors to the degradation of areas in the rangelands. From a pasture condition perspective, invasive native scrub (applicable in areas that are prone to scrub encroachment) are non-preferred ‘increaser’ species that, unless well managed, will dominate the system and reduce its ability to convert water and nutrients into useful feed (palatable green leaf) and consequently animal production.

A decline in landscape function often results in poor responses following rain events.

SIGNPOSTS

READ

Guidelines for the re-introduction and utilisation of high priority native grass species.

Know your options – in good seasons

“Make hay while the sun shines” – these conditions don’t last forever!

Good seasons never seem to happen frequently enough, according to many pastoralists in Australia.

Capitalising on the good seasons takes careful planning, adaptive management, and risk management (and a bit of luck in some cases!).

There are many rules of thumb regarding the impact of the ‘good seasons’ on agricultural businesses across Australia, but importantly, the reality of the good season is that you need to be ready to take the opportunity to benefit from the seasonal conditions, which will help provide the capacity to buffer you against the poor seasons.

Through your experience of good and dry times you will develop an understanding as to how many animals you can comfortably carry on your property. Once you have this figure in mind:

- Know your key dates and trigger points for making decisions (e.g. ‘if it rains by XX date and feed supply is at XX level, we will retain XX% ewe lambs and keep XX% productive older ewes to increase grazing pressure.’);

- Have a plan to utilise the extra feed which grows in good seasons;

- Actively monitor your total grazing pressure and feed supply; and

- State your risks and analyse risk before making any decisions.

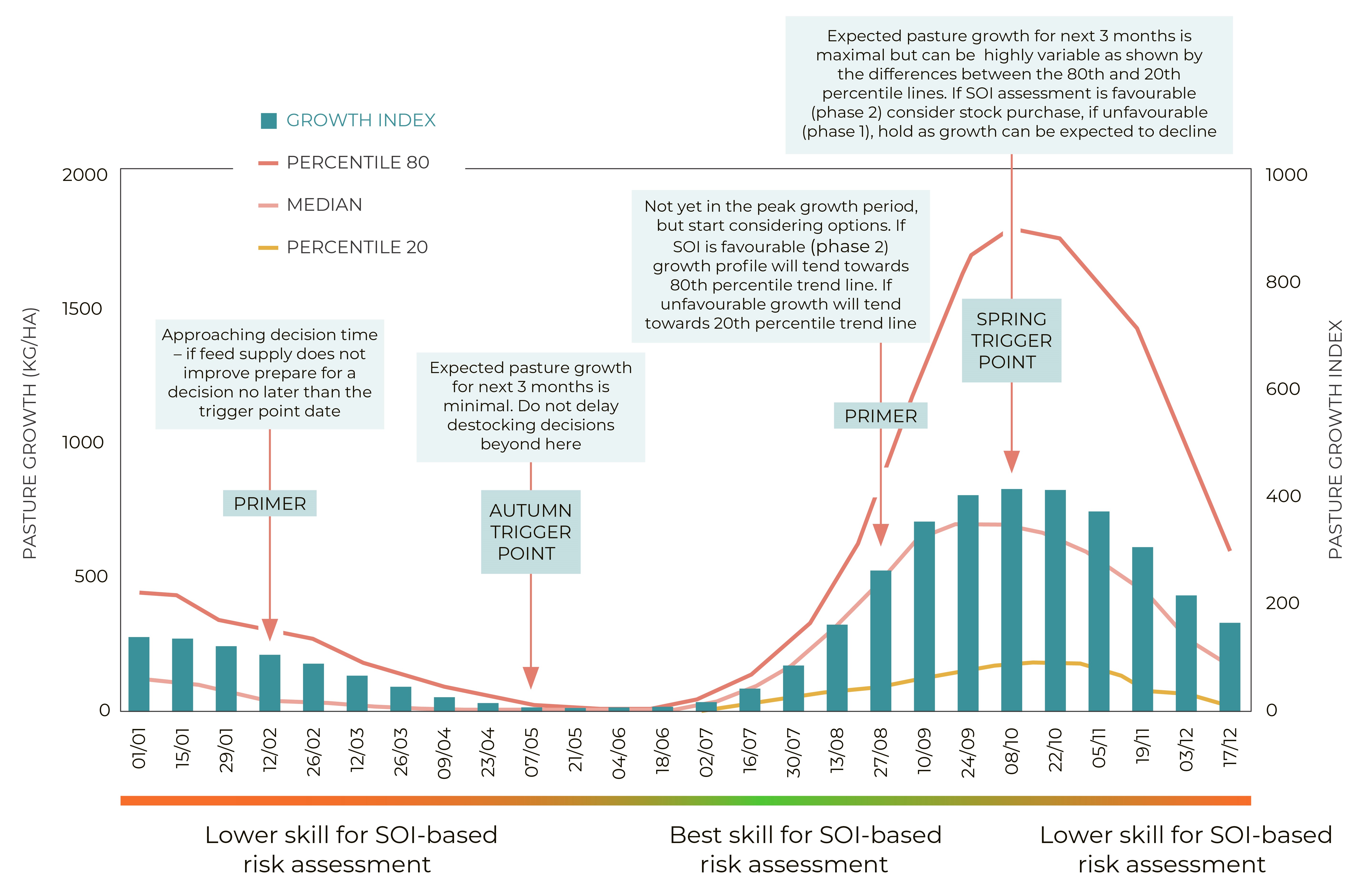

Trigger points are dates determined by the calendar or an external measure (e.g., rainfall received, percentage of feed in the paddock, condition score of ewes) beyond which decisions (e.g., to buy or sell livestock, begin supplementary feeding or move sheep to a different paddock) should not be delayed. They can be identified by long-term simulated pasture growth and rainfall records, coupled with on-ground monitoring and assessments, to show when the prospects for pasture growth for the next three months are highest or lowest and the variability in growth from year to year.

Periodically reviewing and monitoring these trigger points is an important part of the planning process and of emerging from poor seasons in a resilient state – physically, mentally and financially – which allows you to capitalise on the good times.

Use the tools from other chapters to understand your feed resource and what its capacity is in good years. Use this information to develop a strategy as to what options you will take to capitalise on the years when there is more feed to safely utilise than your stock can consume. Some options are:

- Trading;

- Taking stock on for agistment;

- Marketing to different specifications (e.g. finishing sheep rather than selling as stores);

- Carrying feed over;

- Allowing a portion of your property to rest for longer periods;

- Retaining more ewe lambs;

- Purchasing replacement sheep;

- Keeping productive older ewes to join again;

- Accelerated lambing (e.g. joining 3 times in 2 years); and

- Joining ewe lambs.

There are others, no doubt, and you will have access to local information which will best fit your operation.

Be sure to utilise all available sources of information for devising your strategies and improving the number of options you have available to you. Tool 12.12 has more information about stablishing and monitoring trigger points.

SIGNPOSTS

WATCH

Webinars on business management skills which improve the bottom line of sheepmeat, wool and beef producers located in the pastoral region.

READ

The pastoral zone of Australia is vast and there are significant differences in farming systems, access to services, native and pest species, enterprise types and business structures. Although there are these differences, Bestprac demonstrated that all pastoral businesses have techniques, systems or innovations that can be shared across state borders to assist others to improve their skills and knowledge.

Know your options – in poor seasons

Getting through a run of poor seasons requires patience, resilience, and a significant amount of planning.

Similarly, and equally as importantly, to knowing options for good seasons, knowing what options you have available to you in poor seasons and what your trigger points are will enable you to make decisions based on sound knowledge and careful planning, rather than snap decisions based on emotion or panic.

Having a sound plan in place (ideally before the poor season hits) with well-defined trigger points will assist in guiding your thinking, but it is important all members of the business are aware of the plan so they can work towards achieving the business’ targets and making assessments so you know when you’ve reached a trigger point.

Trigger points are dates or times by which something needs to have happened (e.g., rainfall received or time of weaning) or you have to have to take action to mitigate the effect (e.g., sell livestock or begin supplementary feeding). Trigger points are the hard and fast point in time beyond which decisions should not be delayed.

Equally as important as your trigger point is your primer point. The primer point is when preparation to enact the trigger point decision should begin. For example, if seasonal conditions are deteriorating, a decision to sell should not be deferred beyond the trigger point, so it’s critical to have your primer point sometime before the trigger point to allow you to be ready to act. An example of primer points in relation to trigger points is included below in figure 12.7.

Some of the strategies to be considered during poor seasons are:

- Whether to feed or sell;

- The cost of feeding (including feed and labour costs);

- Feeding options (e.g., containment, self feeders, dumps in the paddock);

- Which sheep to sell;

- When to sell; and

- Water volume and security.

By setting your own key dates and trigger points, where you assess the current conditions, seasonal outlook and other factors (including commodity marketing options and price forecasts, risk, resources available to the business, etc.), you can strategically work through the issues in a way that allows you to be in control.

Revisiting and adjusting your trigger points is an important part of the process – keep reviewing your plans and updating them, but don’t put off the inevitable. Early decisions are often the ones made with the least amount of emotion as they are not forced decisions. This is an important part of managing poor seasons and emerging in a resilient state (physically, mentally and financially) ready to take advantage of the good times.

Consider the growth potential and critical percentile profiles and determine trigger point dates as shown in the example below.

Figure 12.7 Example of how to use pasture growth profiles and critical percentile values to determine trigger points beyond which decisions that depend on future feed growth should not be delayed. Note the primer point, some time before the trigger point, when preparation for a decision and consideration of options should start.

Source: Betting on rain – managing seasonal risk in western NSW, adapted by AWI & MLA

Managing your pastures and land condition (landscape function) remains important during dry times, as maintaining function will assist with faster recovery as it will be more ‘rain ready’.

SIGNPOSTS

READ

A range of publications and links to other organisations relevant to managing during a drought.

A number of resources available relating to poor seasons and droughts.

An updated, detailed full-colour guide to farm water supply for stock and domestic use. Learn about water quality stock water requirements, pumps, alternative power sources, pipes, tanks underground water, and more. Save money by choosing the right pump.

Resources from the Australian Government.

Resources from Bureau of Meteorology.

Resources from NSW DPI.

Resources from Queesnalnd Government.

Resources from the Department of Primary Industries and Regions SA

Resources from WA Department of Primary Industries & Regional Development.

Monitor your business

Keeping a watchful eye on the performance of your property and business will ensure that you have a strong handle on the current position of your business, plus you can accurately forecast the next year’s performance under best, average and worst case scenarios.

Natural resource management (NRM) monitoring

Monitoring your property’s assets and performance is as important as monitoring business performance and assets.

There are a number of monitoring systems available for monitoring land condition; refer to chapter 5.4 in MMFS Module 5 Protect Your Farm’s Natural Assets. One of these monitoring systems, The ABCD Land Condition Guide, provides the methodology for assessing the soil condition, pasture condition and woodland condition. This involves assessing the landscape based on an A (high value), B, C or D (low value) rating for a number of different areas including:

- Soil cover;

- Erosion risk;

- Levels of bush, grasses and forbs;

- Levels of recruitment of desirable species;

- Evidence of grazing impact on shrubs and soil;

- Palatable and non-palatable species; and

- Weeds.

Land condition and landscape function have a strong focus in most of the grazing management and landscape monitoring systems. Three well-known approaches to monitoring landscape condition and function are:

- Ecosystem Management Understanding (EMU™) – considers landscape and catchment function and the processes whereby these functions can be restored through grazing management and on-ground works to alter the flow of water through the catchment. EMU involves reading and recognising landscapes, internal linking processes (function), condition and trends (Walton and Pringle, 2010).

- Landscape Function Analysis (LFA) – program developed by David Tongway for both the ongoing monitoring of rangeland environments and rehabilitating degraded areas. Landscape Function Analysis (LFA) allows landholders to assess the results of their management actions and identify future priority areas. LFA challenges the idea that vegetation equals a health landscape and instead focuses on soil condition as the basis for plant growth. A number of system elements are examined to determine where they are stable or unstable (Hannigan, 2007).

- Tactical Grazing Management – and other grazing management approaches provide a range of tools for assessing landscape to guide management decisions, e.g. assessment methods for ground cover and perennial grass utilisation. It also considers approaches to setting a stocking rate, the impact of non-domestic species and changes in shrub cover.

These approaches involve understanding and reading the landscape and identifying indicators of better function, or poorer function and degraded parts of the landscape. These approaches highlight the importance of rangeland ecological function and how it plays an important role in key processes such as infiltration of rainfall received.

Weeds

All good NRM monitoring considers the prevalence, impact and cost of managing weeds. Weeds pose a significant threat to Australian rangeland systems and threaten grassland and woodland condition. In addition to threatening biodiversity through impacts on individual species and communities, they have the ability to downgrade key ecological processes.

The costs associated with weeds can be linked to:

- Decreases in productivity of rangeland systems;

- Contamination of livestock products (wool and meat);

- Damage to livestock (e.g., toxicity, grass seeds); and

- Costs of control, containment or prevention.

There are six principles to achieving effective weed control:

- Detection: be on the lookout for new weed infestations before they become too large and difficult to handle.

- Awareness: be aware of existing and potential weed problems.

- Prevention: prevent new weed infestations and contain the spread of existing weeds.

- Planning: prioritise efforts and plan a strategy for successful control.

- Intervention: control weeds early before they become out of control.

- Control and monitor: control, monitoring and follow-up are all aspects that will assist in achieving good weed control.

Weed management is an ongoing component of property and grazing systems management. See tool 5.3 and tool 5.4 from MMFS Module 5 Protect Your Farm’s Natural Assets for weed management and control tactics.

SIGNPOSTS

WATCH

Working with landholders to reduce erosion which benefits both the environment and a farm's productivity.

READ

Successful graziers use a range of grazing techniques and varying approaches according to the needs of their sheep and pasture throughout the year (or a series of years).

A land management program for pastoralists and other land users to re-cover their land and enhance productivity. EMU introduces land users to the ecological management of landscapes and habitats by learning to recognize and read landscape processes, condition and trend, and to capture rainwater onsite.

Successful grazing managers have the flexibility to move between different grazing methods according to seasonal conditions and livestock demands. These managers can consistently maintain high pasture utilisation without compromising groundcover targets. They tend to calculate seasonal feed budgets and pasture mass targets, which are supported by grazing records and resource monitoring.