Chapter 10.3 Keep maximum number of lambs alive to weaning

Background information

The profitability of high-performance lambing systems depends on targeting those management practices that are cost effective and improve lamb survival. Most lamb loss occurs in the first three days after birth so reducing lamb losses must focus on factors that can improve survival of newborn lambs. As the condition score (CS) of ewes at lambing increases, so does lamb survival, especially in twin bearing ewes.

At a glance

- Select a lambing time likely to maximise survival of newborn lambs.

- Manage mob size for best lambing results.

- Early selection and pasture preparation in lambing paddocks ensures that lambs reach target weaning weights.

Introduction

Important principles to increase lamb survival are:

- Select a lambing time that is likely to maximise survival of newborn lambs.

- Ewe condition at lambing is the most important determinant of lamb survival, due to its effect on lamb birth weight.

- Cold, wet and windy weather increases lamb mortality, particularly with lambs that have a low birth weight. Manage ewes to minimise the impact of weather at lambing.

- Plan to have sheltered paddocks available for lambing. Early selection of lambing paddocks on the basis of size, availability of shelter, and pasture quality and quantity available for ewes are critical management decisions affecting the ability to wean more lambs.

- The effects of prolonged birth and the combination of hunger and mismothering account for the majority of lamb deaths.

- Optimum ewe nutrition in the lead up to lambing will assist the ewe in delivering in a timely fashion, decreasing the risk of dystocia.

- If ewe nutrition is poor, there is delayed production of colostrum and newborn lambs are at risk if they do not receive a drink soon after birth. In addition, mothering ability and lamb behaviour are depressed when ewe nutrition is poor.

- The longer a ewe stays at the birth site, the greater the chance of the ewe and lamb forming a bond, thereby reducing the risk of mismothering.

- Depending on the ewe and the breed type, it takes up to six hours for a ewe to recognise her lamb and in this time a ewe may accept any lamb as her own. It takes lambs twice as long to recognise their mothers and if a lamb is abandoned within six hours of birth it has little chance of survival.

- Ewes about to give birth may ‘pirate’ recently born lambs only to abandon them when their own lamb is born.

- When the number of ewes lambing is at its peak, the lambing paddock is a busy and cluttered place. Best practice is to minimise any disturbance in the lambing flock.

- Primary predation by predators such as foxes, wild dogs and feral pigs can cause significant lamb loss in some situations. They will also scavenge and remove the carcasses of lambs that have died from other causes such as mismothering and hypothermia.

- Studies have shown that fox predation cause between 5-10% lamb loss on average but in some situations it can be as high as 22%.

- The presence of large numbers of predators in and around lambing ewes may cause increased mismothering as the ewes try to avoid predators following birth.

- Participation in coordinated vertebrate pest management programs, as well as targeted control campaigns prior to lambing, is the best insurance to protect against large losses of newborn lambs.

Aim for lamb survival better than:

- Merino ewes: single bearing – 90% survival; twin bearing – 70% survival

- Crossbred ewes: single bearing – 90% survival; twin bearing – 80% survival

As ewe condition score at lambing increases so does lamb survival, especially in twin bearing ewes. In the period from three days after birth to before weaning, aim to keep lamb mortality rates to less than 3%.

Selection of lambing paddocks

Several key features need to be considered when selecting lambing paddocks.

Pasture availability targets

The following pasture targets provide a guide to best practice:

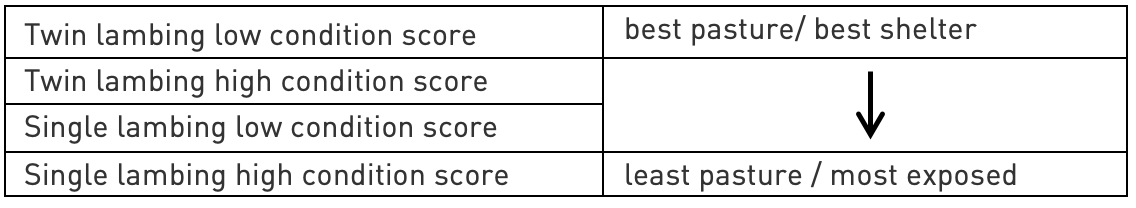

- Where ewes are scanned and drafted into single and twin bearing, allocate ewes to lambing paddocks that have the best pasture/best shelter to least pasture/most exposed on the following basis:

- As a guide, aim for:

- Mixed perennial pastures: FOO of at least 1,300 kg high quality green DM/ha in lambing paddocks, and preferably a minimum of 1,800 kg with twin lambing groups.

- Legume-based pastures: FOO of 1,300-1,800 kg green DM/ha is recommended at commencement of lambing.

- Prioritise the available pasture resources to ensure paddocks have adequate quantity for ewes at lambing.

- If pasture is likely to be limited during lambing, save pasture in early pregnancy or consider adopting strategies to increase pasture production.

- If pasture availability targets cannot be met on a regular basis use tool 10.2 to review your time of lambing.

Lambing paddock shelter

The factors contributing to the risk of hypothermia in lambs include combinations of temperature, rainfall and wind speed. Of these, only wind speed can be controlled by using naturally sheltered lambing paddocks. As a guide, sheltered paddocks can reduce lamb mortality rates by about 10% but shelter will provide less benefit if lambing in locations or seasons with milder weather.

Ideally, lambing paddocks that are sheltered from the prevailing winds and provide shelter over the entire paddock are best for lambing. Satisfactory shelter can be provided by trees, shrubs, pasture, tussocks and rocks. It is important that shelter belts are designed properly otherwise they may act as wind tunnels when grazing livestock remove the foliage from the lower branches (see chapter 5.3 in MMFS Module 5 Protect Your Farm’s Natural Assets).

When selecting lambing paddocks, consider sheep grazing behaviour and paddock characteristics and avoid those where ewes are likely to lamb in exposed areas. Preferred paddocks are those with adequate pasture, north and east facing, have good sunlight in the morning, are well drained and provide good access to water.

Paddocks with low worm risk

In high rainfall regions, gastrointestinal parasites are a major cause of production loss in ewes and poor growth in lambs. Ideally, graze ewes on paddocks with low worm contamination during lambing. Worm management is discussed in chapter 11.2 in MMFS Module 11 Healthy and Contented Sheep.

Paddock and mob size

The most important considerations are to stock lambing paddocks to match pasture availability with breeding ewe demand (see tool 7.6 in MMFS Module 7 Grow More Pasture for a range of pasture assessment tools), and simultaneously reduce twin lambing mob size. A smaller mob size will improve lamb survival due to lower incidence of mismothering.

Many factors must be considered when exploring your options regarding reducing lambing mob size, including the cost of subdivision and management issues with extra mobs. Temporary electric fencing provides a cost-effective method of reducing lambing mob size, while maintaining, or even increasing, stocking rate in your best lambing paddocks.

| Flock type |

Maximum recommended flock size |

| Twin-bearing mature ewes | 150 |

| Single-bearing mature ewes | 500 |

| Single-bearing maiden ewes | 400 |

Predator control

The main predators of newborn lambs are foxes and in some regions, wild dogs and pigs. Predation rates will vary depending on the vertebrate pests present, their density, and other prey on offer. In some situations, foxes and feral pigs can cause significant losses from preying on newborn and young lambs. Feral pigs have been found to cause up to 32% lamb loss in semi-arid sheep enterprises.

Predator management strategies will vary between production systems and environments. A predator management plan for those present in your region should be developed and delivered annually in accordance with the strategies and control tools described in tool 5.7 and tool 5.8 in MMFS Module 5 Protect Your Farm’s Natural Assets. This should include a range of control tools being delivered twice yearly as part of a coordinated program with neighbouring properties, as well as targeted control leading in lambing periods. These periods need to be at least 2–3 months prior to lambing to ensure predator populations are reduced well before lambs start hitting the ground.

Seek advice from the relevant authorities on pest control techniques and coordinated programs in your region as part of the planning approach. Significant assistance is available through these contacts and community lead pest management group as across the country. Case studies and examples of effective integrated control programs are available through AWI, MLA and PestSmart (signposts).

Investigating neonatal lamb deaths

Investigate excessive newborn lamb losses and discuss with your animal health or livestock advisor. Tool 10.9 contains a check list to diagnose common causes of lamb losses so you can improve management to reduce deaths in future years.

Supervision during lambing

Best practice is to minimise the disturbance of the lambing flock. If supervision is warranted, where possible it should be undertaken from a distance using binoculars or a drone. If there is a visible issue requiring attention, the best time to enter the maternity paddock is in the early afternoon. Develop a routine so ewes will become accustomed to human presence and will not leave their lambs. Injured ewes or lambs should be assisted where possible or humanely destroyed.

Lamb marking and mulesing

Losses between marking and weaning are normally less than 1%. Time marking and mulesing for about two weeks after the last possible lambing date. Hygiene is most important for equipment.

Conduct mulesing in accordance with industry guidelines using an experienced operator and appropriate anaesthesia and analgesia (see signposts). If mulesing is conducted when flystrike is possible, treat lambs with a product to prevent flystrike on healing wounds.

Anaesthesia and analgesia should be used for all lamb marking procedures. Consult with your animal health advisor for more information.

Carry out marking and mulesing in clean yards close to the paddock being grazed and ensure the operation is completed early in the day so ewes and lambs can successfully mother up.

For guidelines on additional health treatments, refer to chapter 11.5 in MMFS Module 11 Healthy and Contented Sheep.

Nutritional management of lambs until weaning

To achieve target weaning weights ewes and lambs need to graze high quality pasture. Pasture quality (especially legume content) and quantity are the best indicators of potential lamb growth rates.

If FOO falls below the optimum of 1,300 kg DM/ha of high quality green feed (high proportion of perennials, 30% legume, dead material 10% of total, digestibility of green around 75%) for single bearing ewes or 1,800 kg DM/ha for twin bearing ewes after the start of lambing, supplementary feeding may be necessary. Mismothering losses due to feeding are likely to be lower if paddocks and mob sizes are smaller.

When available feed resources are low, consider identifying ewes that failed to lamb or lost their lamb by wet/drying at marking and removing them to save pasture for lactating ewes. Dry ewes can be managed separately or sold.

Imprint feeding lambs before weaning

Train lambs to feed supplements by ‘imprint’ feeding before weaning. Feed lambs at least 4-6 times while with their mothers (at least 90% of the lambs should be coming to the feed and eating) using the supplements most commonly used on the farm. The idea is to introduce the lambs to feed so they can recognise the supplement after they are weaned.

This is an important management strategy that reduces the period taken to train sheep to eat a supplement once they are weaned and should be undertaken in all seasonal conditions so that your sheep are ready to be supplementary fed when required. Lambs that have been imprinted with their mothers come onto supplementary feed more quickly and eat more of the feed (i.e., their full ration) than sheep that were not imprinted. Research has shown this training lasts up to 34 months of age.

SIGNPOSTS

WATCH

Videos on best practice control methods for pest animal management.

A ten-part video series centred around sheep reproduction. Tune in to hear a range of practical ways growers can influence sheep reproduction with the latest research and tools informed by AWI-funded research and development outcomes.

- Episode 1 – Lambing mob size

- Episode 2 – Weaning to manage

- Episode 4 – Ewe condition scoring

- Episode 6 – Lambing paddock planning

- Episode 7 – Scanning to manage

Lamb survival during late winter and early spring is a critical issue for producers in Victoria's south west, with twin-born lambs most at risk. A project at the EverGraze Hamilton site has used tall wheatgrass rows as an option for producers in a high-risk area to improve weaning percentages.

READ

The impact of wild dogs attacks on livestock across Australia conservatively cost the Australian economy upwards of $89 million a year in lost production and control costs, not to mention the impact of foxes and pigs, as well at the impact of all 3 species on native flora and fauna.

MLA invests in pest management research and development (R&D) to eradicate and control invasive mammals and pests that threaten livestock health and the productivity and profitability of the Australian red meat industry.

National Wild Dog Action Plan resources including a diagnostic tool to understand if dogs are a problem on your property, key contacts in each state, tools for a Wild Dog Management Plan, case studies and an overview of management tools for the control of wild dogs.

USE

Provides information and guidance on best-practice invasive animal management on several key vertebrate pest species, including rabbits, wild dogs, foxes and feral pigs. Information is provided as fact sheets, case studies, technical manuals and research reports.

Map sightings of pest animals and record the problems they are causing in the local area.

Map sightings of pest animals and record the problems they are causing in the local area.

Assists sheep producers proactively manage the nutrition of their ewe flock through the reproduction cycle utilising condition scoring and feed on offer (FOO) assessments.

Assists sheep producers proactively manage the nutrition of their ewe flock through the reproduction cycle utilising condition scoring and feed on offer (FOO) assessments.

This tool provides a systematic basis for planning the management calendar for the breeding flock. The Lambing Planner is available as a hard copy or can be downloaded as an app.

Develop a drought feeding strategy for sheep or cattle by determining feed requirements for different sheep age groups and pregnancy or lactation status.

A community website that farmers, community groups, pest controllers, local government, catchment groups and individuals managing pest animals can use to map sightings of pest animals and record problems they are causing in the local area.

ATTEND

The course is delivered in small groups of 5-7 sheep producers that meet six times per year with a professional trainer. During these hands-on sessions, the group visits each participating farm and learns skills in condition scoring, pasture assessment and best practice ewe and lamb management to increase reproduction efficiency and wool production, mainly through reducing ewe and lamb mortality.

A practical, one-day workshop highlighting the key production benefits of superior genetics, plus feed management for improved reproductive performance and livestock productivity.

This program is delivered as a mix of workshops and on-farm coaching to assist you in building your own plan to improve lamb survival within your business. The first step is knowing where you have come from, knowing your potential, and identifying your opportunities for improvement.

The provision of pain relief with routine husbandry practices is now an expectation, and producers need to consider the use of pain relief products in their animals, but also alternate husbandry procedures and management practices. This MLA module outlines available products, their costs and when they are suitable to use, as well as best practice recommendations for specific husbandry practices, and considerations for alternatives to some current husbandry practices.

Designed for woolgrowers and is aimed at improving weaner management of their Merino flock, targeting 95% weaner survival to one year of age. WWW identifies key practical actions and tools for commercial enterprises to implement on farm to achieve this performance aim.

Assists the commercial self-replacing Merino production sector in recognising and placing importance on the total lifetime productivity potential and value of their Merino ewes (fleece, meat and surplus stock) and identifying ‘passengers vs. performers’.