Tool 11.11 Management of flystrike

Management of flystrike

Flystrike is a costly disease and remains a high priority for the Australian sheep industry. The conditions required for flystrike include the presence of susceptible sheep, the presence of flies and favourable weather conditions for fly development. The severity of the problem varies between regions and between years, depending on climatic conditions.

Young sheep are most at risk as they are often unclassed, can grow greater wool length as they are not pregnant or lactating (leading to more wool around the breech and pizzle) and have not yet developed immunity to worms so can have more dags.

Flystrike control and prevention is based on integrating a range of management tools to reduce sheep attractiveness to flies, including long-term genetic selection for less wrinkly breeches and less daggy sheep, mulesing, crutching, strategic chemical use in the high-risk period and using fly biology to minimise fly numbers.

All aspects of management are important to control flies to reduce production losses whilst maintaining sheep welfare. Strategic management to minimise chemical use is important to reduce the risk of chemical residues as well as reducing the risk of developing resistance.

Reduce the attractiveness of sheep to flies

Correct tail length and mulesing technique

Dock lambs at the third palpable joint of the tail and use the modified mules as indicated in the Plan, prepare and conduct best welfare practice lamb marking procedures training guide. Each state or territory has its own veterinary surgery/practice and animal welfare/prevention of cruelty to animals legislation. The Australian Animal Welfare Standards and Guidelines for Sheep (January 2016) have been adopted by state regulators, and state that a person responsible for the care of livestock must at all times have the relevant knowledge, experience and skills, or be under the direct supervision of a person who has the relevant knowledge, experience and skills.

Lambs destined for slaughter should not be mulesed, and if docked should be done at the correct tail length. The use of pain relief with anaesthesia and analgesia is recommended, and in some states mandated, for certain procedures – consult your veterinarian or sheep health advisor as to the appropriate products and complete MLA’s eLearning module Pain relief use in sheep for more information.

Timing of crutching and shearing

Time of crutching and shearing has a major effect on the risk of flystrike. Crutching or shearing just before the major fly risk time will reduce the need for chemical treatment to prevent flystrike. Crutching before the major fly risk period will prevent breech strike for around 6 weeks. If sheep are scouring and have dags this is more important, however scouring can reduce the period of chemical effectiveness and crutching effectiveness.

Avoid excessive crutch size if dags are low as there is no reduction in risk of flystrike compared with moderate crutch size. A large crutch will reduce fleece values by at least 50 cents/head.

Example of a moderate crutch.

Source: AWI

Ensure you have adequate first aid supplies, veterinary medications and over-the-counter antiseptic sprays on hand when shearing and crutching in case of cuts. Wound treatment sprays that contain antiseptic and insecticide (fly repellent) are preferable (e.g., Centrigen or Extinosad). For more information check out the AWI Dealing with shearing cuts factsheet.

Control worms to prevent scouring

Scouring is a major risk factor for flystrike. Effective worm control will reduce the risk of breech strike.

Selecting sheep for reduced susceptibility to breech strike

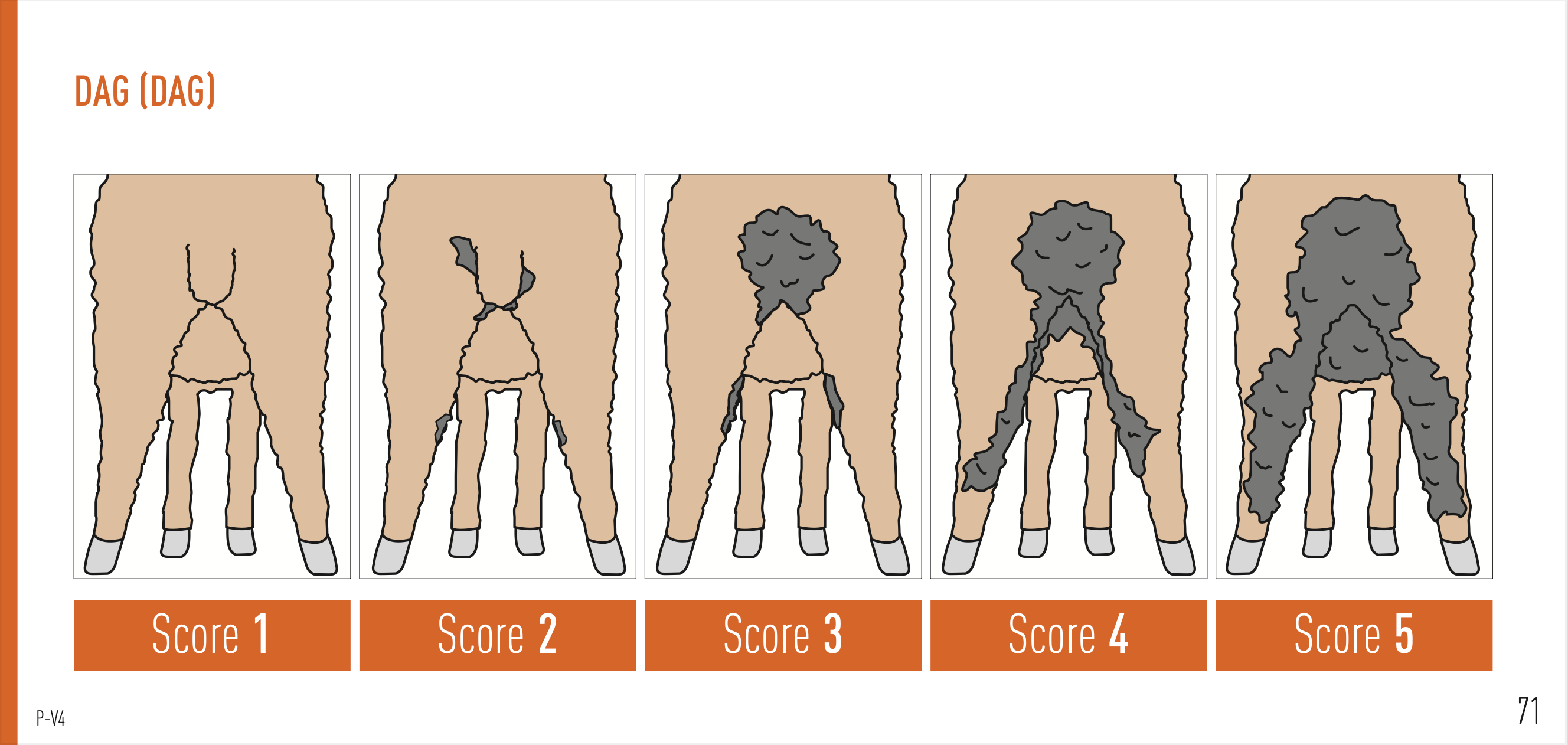

Selecting sheep for low WEC and dag score is heritable and, over time, will help reduce scouring. Selecting for low WEC will reduce worm contamination on pasture and in the longer term, help control worms. Select for low breech wrinkle, since this is strongly related to breech strike and if suitable sheep are available, select for low breech cover. Dags can be the highest breech strike risk factor in winter rainfall dominant regions for several months in winter and spring. Dags are easier to manage on low breech wrinkle sheep. Sheep with low wrinkle, dag, urine stain and breech wool cover can be selected using Visual Sheep Scores and ASBVs.

Target breech scores to reduce the risk of breech strike are 2 score or less for wrinkle, dags and urine stain, and 3 score or less for breech wool cover. The lower the score, the lower the risk of breech strike.

For more information on the causes of breech strike and resources to minimise your risk, visit FlyBoss.

Visual scores for dag.

Source: AWI and MLA Visual Sheep Scores Guide

Select sheep with reduced susceptibility to body strike

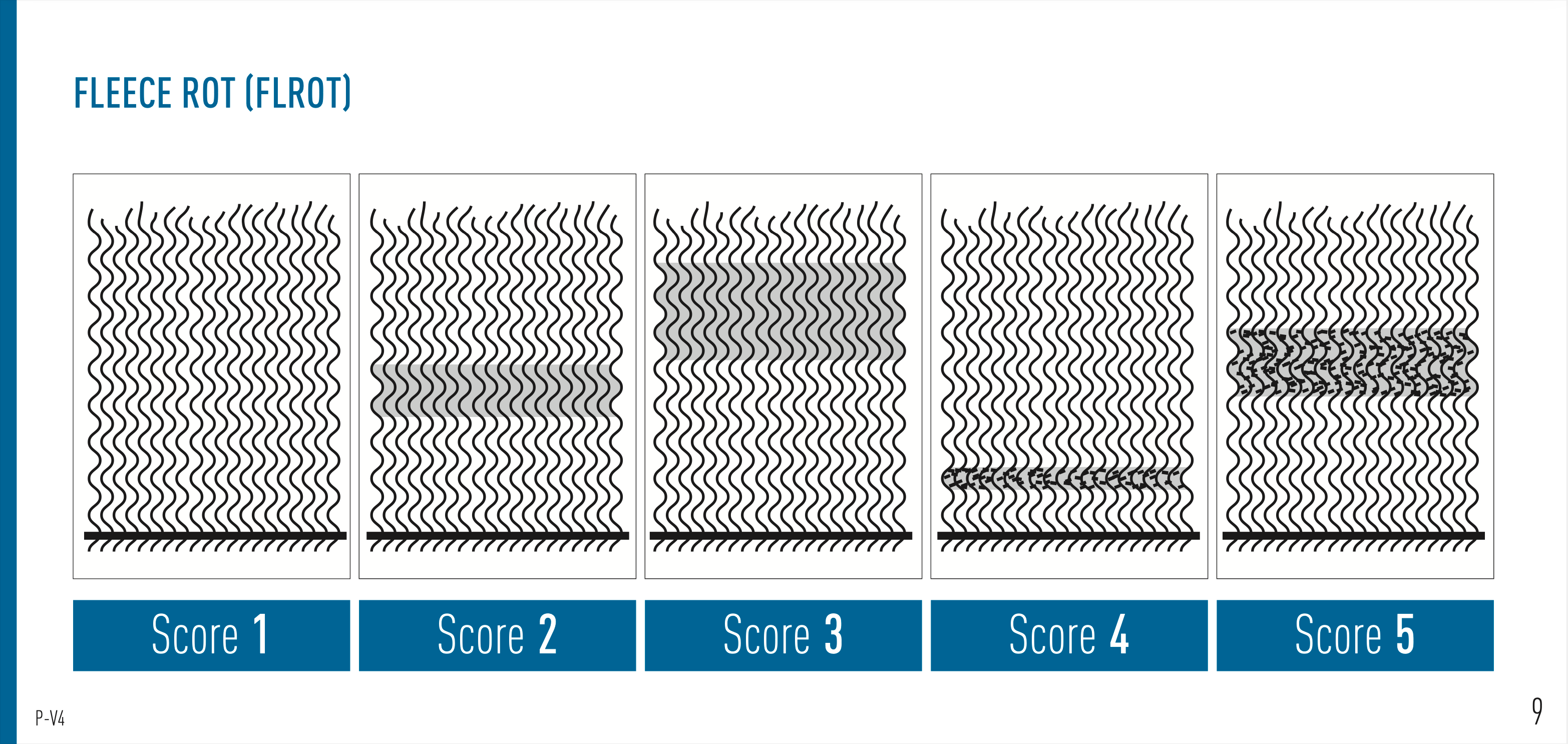

Selecting sheep with less wool colour and less fleece rot will also reduce the risk of body strike.

Research over many years has shown that the most important factor affecting the risk of body strike is the presence of fleece rot. Body wrinkle is not normally associated with increased risk of body strike.

Fleece rot is caused by moisture and bacterial growth at skin level. Fleece rot refers to the degree of wool discolouration and/or crusted banding across wool fibres and parallel to the skin. Discoloured bands can be yellow, green, red-orange, pink-violet, blue, brown or grey in colour.

Fleece rot should not be confused with dermatitis (or 'lumpy wool'), which tends to form columns of hard lumps along the staple. Read AWI’s factsheet Fleece rot and lumpy wool are not the same to understand the symptoms and treatment for the different conditions.

For more information on the causes of body strike and resources to minimise your risk, visit FlyBoss.

Visual scores for fleece rot.

Source: AWI and MLA Visual Sheep Scores Guide

Strategic application of chemicals to prevent flystrike

Spray-on applications of chemical is an important strategy to prevent body and breech strike during high-risk periods. This is especially important when flock supervision is limited. Choice of product needs to be based on length of protection, labour availability, skill level, efficacy, wool length, withholding periods and intervals for wool and meat, and cost.

Managing chemical resistance

Just like in worm control chemical resistance is a concern. These signs typically indicate that your flies might be resistant to chemical treatments:

- a shortening of the protection period that is specified on product labels; or

- flystrike in multiple sheep that have been treated with the same chemical rather than just in a few sheep.

Steps to take to minimise resistance:

- Use a range of chemical and non-chemical tools – consider the timing of crutching, shearing, lambing, drenching and changes in diet to reduce the risk of flystrike. Even a small shift in when you carry out these activities can have a big impact.

- Know the chemical groups and rotate them where practical - chemical resistance in flies is more likely to occur with long term use and over reliance on just one chemical group

- Optimise the number and timing of chemical and non-chemical treatments - when planning how you will manage your flystrike risk, consider the best combination and timing of all activities to extend the protection period. This will likely result in a staggered approach to preventative activities during the season rather than a ‘once only hit’.

- Follow the label directions and keep treatment records - don’t rely on your memory of how to apply chemicals – check the label carefully every time. Also check that anyone applying chemicals to your sheep knows what to do.

- Regularly monitor for flystrike and kill any maggots from struck sheep - treat any struck sheep as soon as possible. Make sure any maggots that are removed from struck sheep are collected and killed to prevent them from developing into the next generation of blowflies, some of which may be resistant to chemical treatments. Fly numbers can increase quickly and dramatically if maggots are not controlled.

For more information on managing blowfly resistance to chemicals visit DemystiFly.

Other strategies to control flystrike

Removal of flyblown material (wool, horns, etc.) and killing all maggots is important to reduce the presence of flies. The killing of maggots and effective treatment of struck sheep also helps address resistance issues where they may occur.

Fly traps can be useful to monitor fly numbers in areas of northern and western NSW and Queensland due to the density of flies at key points (e.g. around the sheep camp). Density of flies in the south in any one place are too low for a fly trap to have a noticeable impact on fly numbers and where sheep become susceptible (for example, due to consistent rainfall) trapping is unlikely to control the fly population enough to have an impact on flystrike.

Fly traps can be useful as an indicator for flies and therefore when to monitor sheep and apply flystrike prevention measures, though this is more relevant for body strike as the main indicator for breech strike and when to monitor sheep is scours/dags.

Paddock selection is also a useful tool for controlling flystrike. Selecting low-risk paddocks for high-risk sheep (such as unclassed weaners, marked lambs, daggy sheep and lambing ewes) is important. Lower risk paddocks are those that are open with more wind, have less timber, ground cover and wet areas and do not have high worm contamination. For more information on low-risk flystrike paddocks visit FlyBoss.