|

|

Devise an action plan with explicit targets and descriptions based on your vision for the resource base.

|

|

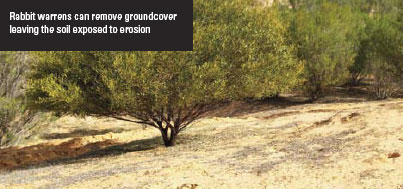

Implement management practices that avoid erosion, not just repair erosion after the event

|

|

Manage stock access to dams and waterways to improve water quality

|

|

Apply the 3Rs of vegetation management - Retain before Restore before Revegetate

|

|

Use integrated pest and weed management methods

|

|

Adopt management practices that help reduce the impact of climate change on your farm |

|

|

Key decisions, critical actions and benchmarks

Prevent soil erosion

Prevent sheetwash and gully erosion by slowing water down, letting vegetation regenerate and groundcover build up. Re-establish riparian vegetation to filter and trap dissolved nutrients and slow water movement. Maintain existing structural works to slow or divert flows where riparian vegetation is in poor condition.

Aim for 70% groundcover in flatter areas and 100% on slopes (see tool 6.2 in Healthy Soils).

This requires management of how hard and long stock are allowed to graze areas. Feed budgeting (see tool 8.4 in Turn Pasture into Product) is a key tool to ensure sufficient pasture is available for livestock production, to determine the number of stock that should be placed in a paddock, and how long they can stay there and maintain groundcover. The signposts contain resources to help you achieve this.

To manage wind erosion, implement management practices that avoid erosion, not just repair erosion after the event. Maintain vegetation cover over more than 50% of the soil surface (see tool 6.2 in Healthy Soils) to:

- Act as a blanket that prevents the wind from picking up any soil particles

- Absorb the force of the wind and reduce the wind speed at ground level

- Trap eroded soil particles and reduce the bombardment of the soil surface.

Stubble, plants, grass butts or small shrubs (higher than 10cm) that sit up into the air offer even more protection, so you will require slightly less cover. Shrubs and tussock grasses protect the soil when the spacing between the plants is less than three times their height, and when they are evenly distributed across the paddock.

The signposts contain a number of useful resources on managing grazing and cropping paddocks in areas prone to wind erosion.

Set targets for what priority areas will look like when you prevent erosion. An example target may be ‘maintain 1,000 kg DM/ha all year round’; or ‘gully walls stabilised’.

Devise an action plan to achieve the targets for each area. Set a date for achieving these targets. Remember it is much easier to break a big issue into smaller, manageable chunks, or individual steps.

Commit to monitoring the change (see procedure 5.4).

Control salinity with best practice

There are two aspects of best practice for salinity management:

- Reduce recharge, then

- Manage saline areas for production and to prevent further environmental decline.

Reduce groundwater recharge with perennial pastures

A CSIRO report summarised the potential of perennial pastures to reduce leakage:

- High rainfall zone (more than 600 mm/year). Near Rutherglen in Victoria, leakage under perennial grasses was estimated to range from 50–120 mm/year depending on grazing management and plant nutrition. Researchers concluded a high proportion of trees would need to be incorporated into the landscape to achieve a significant reduction in recharge

- Medium rainfall zone (400–600 mm/year). Perennial systems can reduce leakage by 20–50% when compared with annuals, but leakage remains 2-3 times greater than leakage under the original woodland. However, lucerne grown continuously can reduce leakage by up to 90%

- Low rainfall zone (less than 400 mm/year). In the Upper South East of SA, lucerne reduced leakage to the level of natural mallee vegetation (<1 year). In western NSW, there appeared to be no increase in leakage on heavier soils when trees were replaced by well-managed grazing systems.

Large scale replanting of catchments to trees is unlikely. To increase water use by pastures and reduce water table recharge rates, use pasture plants which grow longer into the season and explore a greater volume of soil (deeper root systems). Provide the right soil conditions for growth (see procedure 7.1 in Grow More Pasture) to improve water use efficiency.

Perennial pasture establishment can be expensive. However, perennial pastures on recharge areas can deliver multiple benefits to your farm by reducing additions to the water table and increasing pasture productivity.

Set targets for what the outcome of preventing or addressing salinity would look like for the priority areas identified in your inventory (procedure 5.2). Example targets may be ‘plant perennial pasture (or trees) on the mid-slopes’ or ‘implement a simple four-paddock rotational grazing system.’

Devise an action plan to achieve the targets for the priority areas. Set a date for achieving these targets. Remember, it is much easier to break a big issue into smaller manageable steps.

Commit to monitoring the change (see procedure 5.4).

Manage discharge

Saline soils are one of the ‘problem soils’ included in procedure 6.4 in Healthy Soils. Saline soils are included here because saline discharge sites are often associated with water quality problems, eg, salt wash-off into streams and increased erosion, and with the decline and death of native vegetation.

Apply the guidelines in tool 5.5 to better manage any saline sites you identified on the farm.

Manage native vegetation

When managing native vegetation, there are two elements of overriding importance – extent (amount and degree of connection between patches) and condition. Now that you have assessed the condition of your native vegetation (see procedure 5.2), manage the vegetation according to its condition to achieve your vision for your grazing enterprise (see signposts in procedure 5.1).

The following general principles for native pasture management can give both production and environmental benefits:

- Avoid overgrazing: regrowth is slow when pastures have been overgrazed (negative for production) and the diversity of native species will decline (negative for conservation)

- Rotationally graze perennial species: rotational grazing (rather than set stocking) favours perennial plants (native and exotic) over annuals (see procedure 8.3 in Turn Pasture into Product)

- Bare ground benefits many weeds: manage grazing to minimise bare ground, but remember that the forbs and other small non-grass plants that contribute to the diversity in native pastures rely on some bare ground between the tussocks.

Apply the “3Rs” – Retain then Restore then Revegetate - when managing, protecting and enhancing native vegetation and biodiversity on your property. Cost and degree of difficulty increase as you move from:

- Retain: areas of native vegetation that are in good condition are extremely valuable and retaining them in that condition should be the focus

- Restore: the vast majority of remnant vegetation on sheep properties has been altered, reducing its conservation value. Restoration of ‘somewhat degraded’ native vegetation (through changes in grazing management, weed eradication, natural regeneration, or enhancement planting) is much easier than starting from scratch

- Revegetate: while ‘revegetation’ is nominally the last resort, the reality on many properties is there is insufficient native vegetation to underpin a healthy farm ecosystem. Revegetation is most effective if it is used to enhance, enlarge or link existing patches of native vegetation. Natural regeneration is the cheapest and most effective, if there is a bank of seed of all the key species still in the soil. Seed banks will be very low on properties that have been extensively cleared for many years, slowing the pace of natural regeneration.

Set targets for priority areas of native vegetation that describe your desired changes. Example targets may be ‘increase remnant areas by 10ha each year up to X% of the farm’; ‘manage native pastures to increase their perennial content from 40% to 70%’; ‘fence a 1ha area around individual paddock trees to encourage revegetation.’

Devise an action plan to achieve the targets for your priority areas. Set a date for achieving these targets. Remember, it is much easier to break a big issue into smaller manageable steps.

Design for birds

Apply some or all of the ten guidelines for attracting birds to your farm while improving the natural assets on which your grazing enterprise depends:

- Local native vegetation (including native pastures) should cover at least 30% of the total farm area

- Re-create local conditions

- Exclude high-impact land uses from at least 30% of the farm area

- Maintain native pastures and avoid heavy grazing

- Native vegetation cover should be in patches of at least 10ha and linked by strips at least 50m wide

- Manage at least 10% of the farm area for wildlife

- Maintain a range of tree ages

- Leave fallen trees to break down naturally

- Maintain shrub cover over at least one-third of the area within a patch of farm trees

- Maintain native vegetation around water.

While it is preferable to follow the suggestions about size, shape, structure and connectivity of vegetation, even small isolated patches of revegetation provide habitat for some native birds and lay a foundation for future birdscaping endeavours. Some model bird havens started out as barren and degraded landscapes. You’ve got to start somewhere.

Use a diversity of approaches to manage weeds

To successfully manage weeds, choose a diverse combination of weed control activities, targeting the weak points in weed lifecycles. The Diversity table in tool 5.3 will help you scope a range of methods for weed control, then choose the tools you can apply to manage the weeds to achieve the goals you identified using the Deliberation table (tool 5.3). Use the Diligence table in tool 5.3 to keep your weed management plan on track, and make sure you “do it on time, every time”.

The CRC for Weed Management has described five ‘tactic’ groups of interventions (see tool 5.4), where you aim the particular intervention to the weak points in the weed’s armour. Tool 5.4 specifically focuses on weeds in native vegetation, but the principles stated have relevance to pasture weeds in general.

Set targets that describe success in weed management for priority areas. Example targets may be ‘thistles occupy less than 10% of the paddock within five years’; ‘weed spraying costs will be 30% lower within five years.’

Devise an action plan to achieve the targets for the priority areas. Set a date for achieving these targets. Remember, it is much easier to break a big issue into smaller manageable steps

Integrated management of insect pests

Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is the increasingly popular system of managing insect pests by monitoring populations, replacing broad-spectrum insecticides that kill pests and beneficial insects alike with more selective insecticides and using other strategies like baiting and seed dressings.

Farmers who have tested an IPM approach have reduced their reliance on broad acre spraying with direct savings of between $5/ha and $30/ha (see signposts).

Time spent spraying is often replaced with regular monitoring of paddocks. A new level of skill is required to identify the beneficial insects as well as the pests and to know the appropriate strategies to apply. Farmers who have tried an IPM approach say holding your nerve and waiting for the beneficial insects to do their job is the most difficult part.

IPM results are confirming what many have suspected for years – well balanced farms, with a good range of more ‘native’ areas have fewer problems with insect pests in crops and pastures. Implement IPM by:

- Increasing the number and diversity of birds on your property - birds are natural predators of many insect pests

- Establishing windbreaks for animal shelter, NRM benefits, and, with a complex understorey, harbour for predatory invertebrates that prey on insect pests in the adjacent pastures

- Sowing tolerant plant varieties - plant varieties can vary significantly in their tolerance to invertebrate pests, eg, sub clover is highly susceptible to RLEM attack, while gland clover has increased tolerance to RLEM. Sow pasture species with increased tolerance to invertebrate pests to decrease pesticide use

- Applying pesticides at the appropriate time and location. For RLEM, TIMERITE® predicts the optimal date for spraying in spring to minimise insecticide use and to maximise effectiveness (see signposts).

Persist with rabbit control

Review the rabbit control measures analysed in tool 5.6 and use a combination of these. In order of cost effectiveness, poisoning, warren ripping and fumigation are likely to be the most important primary control methods. With rabbits, it’s a matter of persistence.

Set targets for rabbit management. Example targets may be ‘rabbit density will be 60% lower in five years’; or ‘50% of the farm’s warrens are ripped in two years.’

Devise an action plan to achieve the rabbit control targets in priority areas. Set a date for achieving these targets. Remember, it is much easier to break a big issue into smaller ‘manageable chunks’, or individual steps.

Target the weak points in the fox lifecycle

There are a range of control measures for foxes (see tool 5.7), and as for rabbit control, it is often best to use a combination. Foxes are highly mobile so without a coordinated effort with your neighbours, control programs are unlikely to have a lasting impact.

Concentrate baiting efforts in March and August/September each year. Around August/September is when mating season has finished and vixens are actively seeking additional food prior to whelping. Also at this time of the year the fox population is at its lowest. In March, juvenile foxes disperse to find their own territory, displacing older foxes. Well placed baits will be readily taken in March. This concentrated, twice yearly baiting slows the recovery of the fox population, as foxes breed only once a year.

Seek local advice on managing native browsers

Many farms with or near large areas of bushland face significant grazing competition from native animals, especially kangaroos and wallabies. In most cases, these are native animals that have benefited considerably from the creation of extensive grasslands and watering points for sheep and cattle and are often present in greatly increased numbers.

Control of native animals often faces strong community resistance. It is not possible to provide best practice guidelines here because what is appropriate in one jurisdiction can be illegal in another.

In most states, sheep producers can obtain permits to cull if certain native animals are causing damage or economic hardship. In extensive grazing areas, culling is the only viable control method. In more intensive grazing areas where competition from native browsers is high, exclusion fencing can be viable. Local advice is essential, as the type of fencing required varies depending on the animals to be excluded.

Manage stock access to water supplies

There are many good reasons for excluding stock from waterways, including the:

- Damage they can cause to vegetation and stream banks

- Decline in water quality they cause through pugging and fouling

- Damage they can do to favourite fishing, yabbying or picnic spots

- Risk of stock losses or stock straying into neighbouring properties.

Many management options are available to minimise the downsides of direct stock access to water bodies. These actions involve the careful design and construction of:

- Crossing points that allow stock (and vehicles) to cross creeks or other water bodies. These are best located where the slope of the banks is not steep, where the stream bed is firm and, if possible, across a narrow section

- Water access points that restrict stock to a limited number of sites, and can involve ‘strengthening’ the access point with concrete, gravel or logs to minimise pugging. The best water access points have the same basic features as crossing points but they also have minimal shade or shelter to discourage stock from remaining in the area other than to drink.

Visit the "Stock and Waterways" website (www.stockandwaterways.com.au). While the site was produced for NSW, the content is widely applicable for the management and sustainability of riparian land.

Consider reticulated water supplies

Carefully designed reticulated stock watering systems will require more maintenance than other stock water supplies such as dams. However, reticulated systems can provide multiple benefits for production and the environment. Some simple principles include:

- Single watering points in large paddocks lead to uneven grazing. Minimise uneven grazing by locating the trough near the centre of the paddock. In cropping paddocks, troughs are best placed close to fences but away from gateways

- Troughs are best located away from:

- Stock camping areas: to minimise dung and dust contamination andalgal growth

- Trees: sheep will lie down around the trough and prevent timid animals from accessing the water

- Remnant vegetation: overgrazing and nutrient build up in the vicinity of the trough will escalate the degradation of the remnant vegetation

- Steep or erosion prone areas: where the constant trampling will exacerbate any problems

- A shade structure over troughs will limit algal growth, reduce evaporation and keep the water cool, but must be kept to a minimum size to discourage camping.

Multiple benefits from farm water storages

Some farm dams are ideal candidates for the concept of multiple benefits. Good design and management of farm dams and the surrounding vegetation can protect your farm dam, improve water quality and water yield and increase the value of the dam and surrounds for wildlife habitat. Most farms have one or two dams that can provide excellent habitat for a range of wildlife like birds, frogs, mammals and fish.

Restrict stock access to let vegetation establish around the dam. Consider limiting stock to a controlled watering area, or providing a reticulated supply. Stock access to some parts of the dam will benefit birds (like swans and ducks) that prefer open space beside water.

Good groundcover in the dam catchment (not applicable to roaded catchments) will improve water quality by reducing soil, nutrient and faecal contamination and sedimentation. Shelterbelts provide shade and can reduce evaporation from the dam’s surface. Reduce wave action with strategic placement of islands and surrounding vegetation, and allow taller reeds and sedges in parts of the dam.

Another simple (but potentially expensive) way to increase wildlife habitat is to construct a dam island. Add vegetation or dead branches to provide nesting and roosting sites for waterbirds on the island. Next time a dam has to be cleaned out, include an island or a vegetated buffer zone in the new design.

Reduce the impact of climate

change

Review the range of options for reducing

greenhouse gas emissions from your

farm using the FarmGAS calculator (see

signposts in procedure 5.2).

A sheep enterprise can either:

- Reduce emissions from livestock

- Offset livestock emissions by storing

more carbon in the landscape.

Reduce emissions from sheep

The key to reducing livestock emissions

is to maximise their growth rates and

convert as much of their energy intake

as possible into meat and fibre. This can

also increase profit.

Research underway at the Sheep

Cooperative Research Centre (CRC)

showed:

- Daily methane production of sire

groups was related to their liveweight,

liveweight gain and feed conversion ratio,

but not feed intake

- Australian Sheep Breeding Values

(ASBVs) for yearling liveweight (YWT)

are positively correlated with daily

methane production.

Selective breeding (see procedure 9.1

in Gain from Genetics), improved feed

management (see procedure 8.2 in Turn

Pasture into Product), maximising

animal health (see procedure 11.2

in Healthy and Contented Sheep)

and improving livestock genetics (see

procedure 9.2 in Gain from Genetics)

are essential to the future profitability

and sustainability of the livestock

industry and the environment.

Store carbon in the landscape

Organic carbon stored in soil is

a significant carbon sink, and is

increasingly recognized in strategies to

mitigate climate change.

Soil can store around 50-300 tonnes C

per ha, equivalent to 180-1100 t CO2.

Pastures and crops store 2-20 tonnes C

per ha, while plantation forests can store

up to 250 tonnes C per ha.

Maintain groundcover (see procedure 6.2

in Healthy Soils) to minimise erosion

losses, maximise organic input to soil,

and offset methane emissions from your

sheep enterprise.

Inclusion of soil carbon management

in any future carbon reduction scheme

will rely on the development of costeffective

methods for estimating soil C

change under changed land management

practices.

Signposts  |

Read

Sustainable Grazing – a producer resource: this section of the MLA website provides a collation of proven best practices for modern grazing enterprises in southern Australia. www.mla.com.au/research-and-development/environment-sustainability/sustainable-grazing-a-producer-resource

The Land section of the Australian Wool Innovation website has information and case studies relevant to sheep producers on a range of natural resource management issues under the headings of soil, water, biodiversity and regenerative agriculture. Visit https://www.wool.com/land/

There are many publications that can

be downloaded that deal with managing

natural resources on farms under the

following headings:

- Native vegetation and biodiversity

- Rivers and water quality

- Sustainable grazing on Saline land

- Managing Pastoral Country

- Managing climate variability

On-farm water reticulation guide:

practical, technical advice to help sheep

producers plan, design and install piped

systems. Order a hard copy from: www.gwmwater.org.au, or click here to download.

Farm Dams: Planning Construction

and Maintenance (2002), by Lewis, B.

Landlinks Press. Buy on-line at: www.fishpond.com.au

View

Greening Australia – Visit: www.greeningaustralia.org.au and select publications.

The PestSmart Toolkit (www.pestsmart.org.au/) provides information and guidance on best-practice invasive animal management on several key vertebrate pest species including rabbits, wild dogs, foxes and feral pigs. Information is provided as fact sheets, case-studies, technical manuals and research reports. Also, view the PestSmart YouTube Channel (www.youtube.com/PestSmart/) for video clips on best practice control methods for pest animal management.

Stock and Waterways - visit the Stock and Waterways website (www.stockandwaterways.com.au). While the site was produced for NSW, the content is widely applicable for the management and sustainability of riparian land.

Review tips on managing wind erosion

under grazing and cropping at:

Weed Management A range of

publications and resource on weed

management can be found at https://www.environment.gov.au/biodiversity/invasive/weeds/

Weed Smart: An initiative to minimise herbicide resistance. Visit: https://weedsmart.org.au/

3D Weed Management publications:

guidelines for identifying and managing

African Love Grass, Chilean Needle

Grass, Paterson’s Curse, thistles, Serrated

Tussock, and Silver Leaf Nightshade. Free

copies of the management fact sheets are

available by:

Downloading from: http://www.wool.com/on-farm-research-and-development/production-systems-eco/pastures/weed-and-pest-management/

WEEDeck: over 200 identification cards

with photographs to identify a range

of Australian weeds. Purchase your

copy from www.sainty.com.au/publications.html

SALTDeck: 50 colour cards to help you

identify and select saltland plant species.

Puchase your copy from www.sainty.com.au/publications.html

TIMERITE®: a reliable and effective

option for control of redlegged earth

mites (RLEM) on your farm. Visit the

AWI website at www.wool.com and search for Timerite.

Grain & Graze Integrated Pest

Management: recent results show IPM

systems can increase biodiversity on

mixed farming enterprises and reduce the

environmental impact of the business. Download the Grain & Graze Integrated Pest Management brochure here.

MLA Tips & Tools: a range of

publications area available covering

weed management, NRM, grazing

management, native pastures, soil health,

deep drainage, groundcover.

Get your free copies from MLA by:

Regional NRM Authorities: critical

links for natural resource management

and funding – for access to all regional NRM

Authorities across Australia go to www.nrm.gov.au/regional/regional-nrm-organisations .

The Australian Government provides grants and financial assistance programs to businesses and individuals to help boost productivity and exports. For further information visit: www.agriculture.gov.au/about/assistance-grants-tenders

Australian primary industries

transforming for a changing climate:

the CSIRO Climate Adaptation Flagship

is working to understand how primary

industry businesses, communities and

sectors can transform their practices to

adapt to climate change. Visit: www.csiro.au and search for Climate Adaptation.

State agency climate change resources:

some state specific resources on the

impact of climate change, and adaptation

options for sheep producers. Visit:

Greenhouse in agriculture: a website

from the University of Melbourne

with a range of spreadsheet tools for

calculating greenhouse gas emissions

from agricultural enterprises, including a

specific spreadsheet for sheep enterprises.

Visit: www.greenhouse.unimelb.edu.au/

Greenhouse gas abatement and feed

efficiency: the latest findings from

Sheep CRC research into tools to help

sheep producers manage greenhouse

gas emissions from sheep. Visit: http://www.livestocklibrary.com.au/search and search for Sheep CRC, select Project Unpublished Reports, then Project 1.4.

Attend

The MLA EDGEnetwork® program is coordinated nationally and has a range of courses to assist sheep producers. Contact can be made via:

|

|